An Ever-Evolving Art Form by Shean O’Nahan

Jeff Wall’s A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993 Photograph: Jeff Wall

Facebook was launched in February 2004. By November 2011, an estimated 100 billion photographs had been shared via the social network. By April 2012, Facebook users were posting photographs at the rate of 300 million per day.

Leaving aside the estimated 11 billion photographs uploaded to image-based sites such as Flickr and Instagram, we have already entered a realm where the numbers are so vast they begin to lose their meaning.

In a feature on new trends in photography, published in Frieze magazine in November/December 2011, the American artist and writer Chris Wiley made a direct link between the post-digital image overload and photography’s ongoing crisis of meaning: “It is indisputable that we now inhabit a world thoroughly mediatised by and glutted with the photographic image and its digital doppelganger. Everything and everyone on Earth and beyond, it would seem, has been slotted somewhere in a rapacious, ever-expanding Borgesian library of representation that we have built for ourselves. As a result, the possibility of making a photograph that can stake a claim to originality has been radically called into question. Ironically, the moment of greatest photographic plenitude has pushed photography to the point of exhaustion.”

Photography, it seems, is experiencing a prolonged crisis concerning not just its role of depicting the world around us – through portraiture, reportage or documentary – but its form and its function, its very meaning.

The creative response has been, to say the least, interesting. In 2011 Michael Wolf received an honourable mention in the World Press Photo awards for photographs that he had selected from Google’s Street View, photographed on his computer screen, cropped and blown up. Is Wolf a photographer? Or is he a curator of images? Or is he, as photography’s purists (of which there are many) would have it, simply another conceptual chancer?

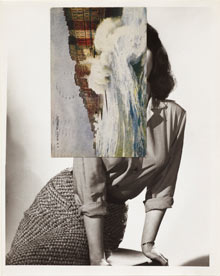

John Stezaker’s Siren Song V (2011) Photograph: John StezakerIn September 2012 the prestigious Deutsche Börse photography prize was won by John Stezaker, who doesn’t take photographs at all. Instead, he works with found photographs, most often publicity stills of long-forgotten film stars, which he slices then merges with other stills to make uncanny collaged portraits that seem surrealist in intent. Stezaker would be the first to say that he is not a photographer, but an artist who uses photography in his creative practice and, in doing so, interrogates the medium and its role as a so-called documenter of truth, reality and celebrity culture.

John Stezaker’s Siren Song V (2011) Photograph: John StezakerIn September 2012 the prestigious Deutsche Börse photography prize was won by John Stezaker, who doesn’t take photographs at all. Instead, he works with found photographs, most often publicity stills of long-forgotten film stars, which he slices then merges with other stills to make uncanny collaged portraits that seem surrealist in intent. Stezaker would be the first to say that he is not a photographer, but an artist who uses photography in his creative practice and, in doing so, interrogates the medium and its role as a so-called documenter of truth, reality and celebrity culture.

The previous year’s Deutsche Börse shortlist featured the work of Thomas Demand, another artist who uses photography but in a very different way, creating lifesize models of real rooms and offices that are loaded with historical or social significance in terms of recent German history. He then photographs the created sites, which are often blankly unreal and denuded of detail, before destroying the models. The photograph is the only existing record of a bigger conceptual process.

Consider, too, the work of one of the giants of contemporary American photography, Gregory Crewdson, whose elaborately staged tableaux often resemble cinematic dreamscapes.

In different ways, the work of all of these artists is about the nature of the photographic – the making of the images, rather than the taking of a photograph. Here, as with much conceptual art, the process seems to be as important as the end result. How cruelly ironic, then, that we are simultaneously witnessing the sudden death of the process that has defined photography for so long, a procedure that began with the insertion of a roll of film into a mechanical camera and ended, via the contact sheet, the dark room and a tray of chemicals, with the printing of a single image on photographic paper.

The tsunami of digital technology has swept away, or is threatening to sweep away, so much that was not that long ago taken for granted: rolls of film, the film camera, dark rooms, processing labs, contact sheets, Polaroids and Kodachrome. As with recorded music and, imminently, printed matter, photography is a world in which all that once was solid is becoming immaterial.

And yet, for all that upheaval, photography, in all of its forms, continues to prosper. There are currently more than 100 annual photography festivals worldwide, from Brighton to Bamako and beyond, as well as several big photo fairs such as Paris Photo, Miami Photo Fair and the just launched Unseen in Amsterdam. Meanwhile, in London and New York, over the past decade or so, a host of new photography galleries have opened. This year the Photographers’ Gallery – Britain’s main exhibition site for contemporary photography – reopened in a newly redesigned building in the centre of London.

There is an attendant flourishing trade in photography books, whether vintage or new, and a burgeoning self-publishing scene. At Tate Modern, meanwhile, the first curator of photography, Simon Baker, was appointed in 2009. If photography is undergoing a potentially terminal crisis, it appears to be a vibrant, exciting and innovative one.

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still, 1978 Photograph: Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New YorkConsider, too, the rarefied world of the global art market, where the dealers and collectors who made pop stars out of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have belatedly canonised the likes of Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman with often hair-raisingly high prices. If you want to know how swiftly and radically things have changed at that level, the prices, as ever, are a good indicator. Back in 2006 the most expensive photograph in the world was a pictorial landscape, The Pond – Moonlight by Edward Steichen, which fetched £1.6m at auction. Taken in 1904 by an early pioneer of the form, it is photography’s equivalent of an old master. The following year, though, a photographic print by Andreas Gursky, entitled 99 Cent II Diptychon (2001), fetched £1.7m – the tipping point in terms of contemporary art photography’s commercial ascendency.

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still, 1978 Photograph: Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New YorkConsider, too, the rarefied world of the global art market, where the dealers and collectors who made pop stars out of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have belatedly canonised the likes of Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman with often hair-raisingly high prices. If you want to know how swiftly and radically things have changed at that level, the prices, as ever, are a good indicator. Back in 2006 the most expensive photograph in the world was a pictorial landscape, The Pond – Moonlight by Edward Steichen, which fetched £1.6m at auction. Taken in 1904 by an early pioneer of the form, it is photography’s equivalent of an old master. The following year, though, a photographic print by Andreas Gursky, entitled 99 Cent II Diptychon (2001), fetched £1.7m – the tipping point in terms of contemporary art photography’s commercial ascendency.

At present, the three most expensive photographs in the world are by living conceptual artists: Jeff Wall, Cindy Sherman and, at the top of the league, Gursky, whose print Rhein II (1999) fetched £2.7m in auction at Christie’s New York in November 2011 (below). It is, for the time being, the most expensive photograph ever. It is also, sceptics might say, one of the most uninteresting photographs ever: a large-format landscape in which the river Rhine sits between two swaths of green grass under a grey sky. Like several of Gursky’s works, Rhein II is a digitally manipulated image – a factory building and some dog walkers were removed from the original photograph by a high-end version of Adobe Photoshop. When asked to comment on this, Gursky said: “Paradoxically, this view of the Rhine cannot be obtained in situ, a fictitious construction was required to provide an accurate image of a modern river.”

Andreas Gursky’s Rhein II fetched £2.7m last year, setting a record for any photograph sold at auction. Photograph: Andreas Gursky/AP Photo/Christie’sMake of that what you will, but the fact remains that the most expensive landscape photograph in the world right now is of a scene that never existed.

What, then, of photography that is not primarily concerned with the photographic or the conceptual? What of documentary, reportage, portraiture and street photography? These more traditional forms are thriving too, and being constantly reinvented in response to the relentlessly mediated world we inhabit. Increasingly, the lines between genres are becoming blurred, though. Is Paul Graham, winner of the 2009 Deutsche Börse prize and the 2012 Hasselblad award, a documentary photographer or an art photographer? Or is he neither? Or both? Are the large-format, inordinately detailed works by Mitch Epstein in his American Power series, or Edward Burtynsky in his Oil series, part of the landscape tradition or the documentary tradition? Is the term “street photography” an adequate description of the urban lightscapes captured by Trent Parke?

Do these generic terms even matter any more in the (post-) modern world? Where do we place the luminously intimate work of Rinko Kawauchi or the often provocative “conceptual documentary” style of Pieter Hugo? Photography is adapting to survive – as it always has.

The coming of the cheap, relatively complex digital camera and the smartphone means we are living in the age of the techno-amateur. This has undoubtedly changed the world of photography on one level: there are millions – billions! – more images being made, shared and stored than ever before.

One sometimes wonders what the future holds for reportage in the age of citizen journalism, in which a single dramatic image can be captured on a bystander’s mobile phone camera and instantly broadcast around the world over the internet. The shooting of the Iranian anti-government protestor Neda Agha-Soltan in June 2009 was captured in this way and became the most widely witnessed death in history.

For all that, no amount of technology will turn a mediocre photographer into a great one. Nor, in conceptual terms, will it transform a bad idea into a good one. For that you would still need to possess a rare set of creative gifts that are still to do with seeing, with deep looking.

Photography, like print media and music, is certainly at a turning point, as the current art market most dramatically shows. But it was also at a turning point during the early- to mid-1960s, when artists such as Andy Warhol and Ed Ruscha were questioning its traditions and its modes of representation through the use of photographs in their artistic practices. You could even argue that Ruscha’s artist’s books of serial photographs, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) and Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), are among the most influential postwar photography books.

Whatever upheavals it has witnessed, photography has endured. It continues to do so, even as we drown in a sea of uploaded images whose sheer quantity mediates against their meaning. Photography, in more ways than one, thrives on a crisis. The instant endures.